Live Cattle Auctions Make a Comeback Online

December 17 2016 - 7:29AM

Dow Jones News

By Kelsey Gee

Unruly trading of cattle futures is leading to a revival of live

auctions, as ranchers look to bring robust pricing data to the

market and guide understanding of supply and demand in their

industry.

Cattlemen trade futures, or contracts to buy or sell cattle at a

given price on a future date, as a form of insurance on their

borrowings to feed hundreds or thousands of animals at a time. In

the past year, values of cattle futures contracts have swung

wildly, from near-record highs to six-year lows.

A nearly one-third drop in the price of cattle futures through

the fall of 2016 has slashed ranch incomes and prompted

investigations into the source of the volatility.

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange is considering drastic changes

to how those contracts are settled. The world's largest futures

exchange has been working with cattlemen to address the apparent

breakdown in the $13 billion market, proposing among other measures

a new index to guide pricing of futures contracts.

CME Group Inc. says an index could help align futures contracts

with real trade data. The index could be built on cattle purchase

prices that meatpackers are required by law to disclose to the U.S.

Department of Agriculture.

Some ranchers say such a price index would make volatility in

the futures market worse. USDA price reports can lag behind actual

deals by hours or even days, meaning the index might not represent

current sales.

Nonetheless, the reports "do provide transparency to the

market," says Dave Lehman, CME's managing director of commodity

research.

The lack of public bartering and price transparency in the

cattle industry is one major source of the market's problems, CME

says. At present, the predominant way of selling cattle is via

private production contracts between feedyards and the four big

U.S. meatpackers. So-called formula contracts price cattle ahead of

sale based on the benchmark price independent cattlemen will get in

the cash market, plus or minus premiums and discounts.

Some feedyard operators now are experimenting with live

auctions, returning to doing business in an open cash market. They

want to generate new public price information and slow the supply

of previously committed cattle to slaughter each week.

"We would rather be a part of the solution than have the

Mercantile Exchange make the decision for us," says Surcy Peoples,

director of customer service at Cactus Feeders, a large cattle

producer in Amarillo, Texas, which before this fall sold most of

its more than a million cattle annually using formula

contracts.

Cactus Feeders is one of nearly 100 producers using Superior

Livestock Auction LLC's Fed Cattle Exchange. In its live-streamed

online auctions, similar to eBay, cattlemen haggle with meatpackers

over fractions of pennies a pound.

Ranchers worry that such auctions still won't generate robust

price data and CME might decide to settle cattle futures prices to

an index anyway. An index system is already in use in the hog

market, which has few remaining independent farmers actively

negotiating for cash.

A cattle index also would eliminate the ranchers' option of

settling futures contracts by delivering cattle -- thus removing

actual animals almost entirely from a financial market created to

assess their value.

"We believe moving to this form of contract settlement

drastically increases the incentive for price manipulation," Craig

Uden, of the National Cattlemen's Beef Association, wrote to CME in

November.

CME says any cash index would be vetted for the reliability of

its data.

The chicken industry also is confronting pricing concerns. An

index called the Georgia Dock has consistently reflected higher

prices than other benchmarks. Georgia's Agriculture Department last

month suspended the index, amid recent scrutiny.

Online cattle auctions have already led to an uptick in cash

sales. The share of steers and heifers sold in cash markets rose to

26% through November this year, up slightly from 21% a year earlier

but still well below a decade ago, when more than half of cattle

were sold in cash markets.

The structure of the industry has changed, and having just a

handful of cash transactions once or twice a week doesn't provide a

good benchmark for the industry, CME says. Negotiations for cash

sales used to take place daily in raucous livestock auction barns;

traders got a sense of fair value at any given moment.

Now, every Wednesday morning, the Fed Cattle Exchange streams a

spreadsheet showing seller, weight and location as each animal

comes up for sale. Bidding starts at a floor set by the producer.

Pictures of the feedyard pops up on screen; prices flash yellow as

bids increase.

"It's important that the public is able to see the transactions

take place on their computer, right in front of their eyes," says

Sam Hughes, manager of the Oklahoma City exchange.

Write to Kelsey Gee at kelsey.gee@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 17, 2016 07:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

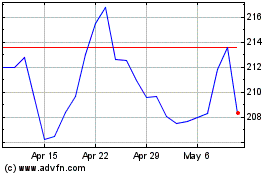

CME (NASDAQ:CME)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

CME (NASDAQ:CME)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024