Amgen's Repatha Study Shows Reduced Risk of Heart Attack, Stroke -- 3rd Update

March 17 2017 - 7:48PM

Dow Jones News

By Jonathan D. Rockoff and Betsy McKay

Amgen Inc. on Friday reported widely anticipated data on its new

cholesterol-lowering drug Repatha, showing it reduced the risk of

deaths, heart attacks and strokes. But the positive findings failed

to persuade Wall Street that health insurers would begin easing

access to the expensive drug.

A 6.4% drop in Amgen's share price on Friday underscored a

mounting challenge for drug companies once they have secured

regulatory approval for a new medicine: getting health plans to pay

for it.

Researchers found, in a study following 27,564 patients over 2.2

years, that Repatha reduced the risk of deaths, heart attacks and

strokes by 20% compared with standard treatment with statin drugs.

Repatha lowered the risk of a wider array of heart-related events

by 15%.

The risk reduction, although significant, may still not be

enough to overcome reservations about a drug that lists for more

than $14,500 a year, according to analysts.

"It is likely that the majority of restrictions" on coverage

such as requiring prior authorization, will remain, Barclays

analyst Geoff Meacham said in a research note.

To persuade health plans and drug-benefit managers to pay for

Repatha, Amgen has offered to refund the cost to payers for

patients who suffer a heart attack or stroke. About 4.9% of trial

subjects suffered one of the events, Peter Bach, director of

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center's Center for Health Policy

and Outcomes, said after reviewing the trial data.

"Now that Repatha has proven a meaningful reduction in

cardiovascular events, we expect payers to remove onerous barriers"

to patient access, Joshua Ofman, an Amgen senior vice president,

said Friday.

In 2016, Repatha sales totaled $141 million, including $101

million in the U.S.

Amgen has been striking so-called value-based reimbursement

deals with health plans like Cigna and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care

that tie the payments the company receives to the benefits to

patients.

Repatha, among the new injectable cholesterol-fighting agents

known as PCSK9s, was approved in 2015 after studies showed it cut

levels of bad cholesterol. Unclear was whether that LDL-cholesterol

reduction also reduced the risk of heart-related events, such as

heart attacks and strokes.

Without such evidence, health plans have limited access to

Repatha, as well as to rival drug Praluent from Sanofi SA and

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., in favor of much-cheaper statin

pills. Shares in Sanofi and Regeneron also fell Friday.

Amgen said last month that Repatha had met the goals of its

study, but released the specific findings only on Friday at a

medical meeting.

Amgen is "very confident" that doctors will view the results as

"practice-changing" and incorporate Repatha into their care of

patients whose cholesterol remains high despite treatment with a

statin or who can't tolerate a statin, said Sean Harper, Amgen's

chief of research and development.

Cardiologists who weren't involved with the study said the

health-plan paperwork required to get a prescription filled for a

PCSK9 drug like Repatha has proven too time consuming for many

practices, deterring prescriptions. The doctors also said that

determining which patients can benefit most from PCSK9 inhibitors

will still be critical, given their cost.

"We have to be very careful; this is very expensive stuff," said

Valentin Fuster, director of Mount Sinai Heart and

physician-in-chief at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. "We have to

be sure we identify the right people for whom this type of approach

would be meaningful."

In making its case to the payers, Amgen may point to the study's

finding that the risk reduction improved after giving Repatha six

months. After a year's treatment, patients taking Repatha were at a

25% lower risk of heart-related events, Dr. Harper said.

Marc Sabatine, the Amgen-sponsored study's lead researcher, said

he expects that Repatha's benefits will increase over time, as they

did for statins. The risk of heart attack or stroke was reduced 19%

in the first year of the Repatha study and 33% beyond the first

year, suggesting a delayed effect of lowering LDL cholesterol, said

Dr. Sabatine, a cardiologist at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and

Women's Hospital in Boston.

Most statins were studied for five years, compared with 2.2

years thus far for Repatha, Dr. Sabatine said. The researchers are

now following more than 6,000 study patients in an extension of the

study to examine the drug's safety, and plan to monitor the

longer-term effects of the drug in more patients, he said.

Write to Jonathan D. Rockoff at Jonathan.Rockoff@wsj.com and

Betsy McKay at betsy.mckay@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 17, 2017 19:33 ET (23:33 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

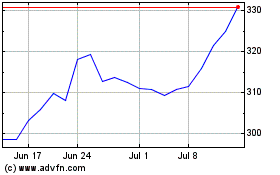

Amgen (NASDAQ:AMGN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

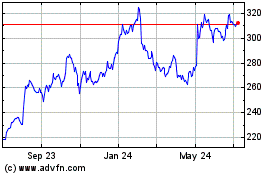

Amgen (NASDAQ:AMGN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024