EU's Tax Decision Invites More Scrutiny of Apple

August 31 2016 - 5:22PM

Dow Jones News

By Natalia Drozdiak

BRUSSELS -- When the European Union's antitrust chief Margrethe

Vestager ruled this week that Apple Inc. owed billions of euros in

alleged unpaid taxes, the decision created a financial and public

relations problem for the technology giant. It also opened up a

Pandora's box of legal questions for Apple and other multinationals

operating in Europe.

Apple has said it would appeal the decision -- as has Ireland,

which the European Commission accused of forging a sweetheart tax

deal with the iPhone maker, in violation of the bloc's prohibition

against "state aid" for selective companies. Both of those legal

challenges could take years.

The decision also opens the door to further scrutiny of Apple

finances, legal structure and tax payments by national governments

across the continent. Ms. Vestager specifically invited them to do

so, saying governments in Europe, as well as the U.S., could claim

a piece of the roughly EUR13 billion, or about $14.5 billion, in

taxes that the commission has estimated Apple avoided paying in

Europe and has ordered Dublin to recoup.

Ms. Vestager's move to inspire other European governments to

undertake their own audits into how Apple paid taxes across Europe

plays into the commission's wider strategy of aiming to close down

tax havens and loopholes in the bloc. The job of actually

identifying any back taxes owed and getting it back into national

coffers would be up to the respective national authorities, Ms.

Vestager said.

A number of individual countries are already investigating

whether rival multinationals paid enough tax. In one of the highest

profile cases, France has been investigating whether Google parent

Alphabet Inc. owes back taxes. Alphabet has said it paid its fair

share.

Apple hasn't been targeted by any country in the EU in

tax-related investigations.

The European Commission invited folk "to come forward and try to

claim a piece of this settlement...so we anticipate that that may

happen and a feeding frenzy may occur," said Jennifer McCloskey,

director of government affairs at ITI, a U.S.-based technology

industry trade group, which represents Apple and other tech

companies.

Apple comment wasn't immediately available.

So far, no other government has said publicly they are

considering the option.

One factor that may limit any claim from elsewhere in Europe:

Most tax authorities in European countries, as well as in the U.S.,

can only seek to claw back taxes for about three or four years

back. The commission's ruling, on the other hand, covers 10 years

under the bloc's state-aid rules.

Some lawyers say if other capitals pursue their own back-tax

claim, they would face big hurdles. The commission has focused its

ruling on what it alleges was Apple's profit shifting from a

taxpaying affiliate in Ireland to its nontaxable, nonresident Irish

affiliate. In its ruling, the commission didn't focus on whether

Apple paid sufficient taxes for its affiliates in other EU

countries, said Howard Liebman, a Brussels-based tax partner at

Jones Day.

"To my mind, that doesn't really give an open invitation to

other EU countries," Mr. Liebman said.

U.S. officials roundly condemned Ms. Vestager's actions, making

it unlikely they would agree to try to benefit from the ruling.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew on Wednesday said the EU's

decision "reflects an attempt to reach into the U.S. tax base to

tax income that ought to be taxed in the United States."

Apple or Ireland, however, could upend the commission's decision

altogether if either wins their appeals in court. Barring an

outright decision to overrule the commission's decision, Apple

could win court backing for a smaller claw back.

The commission's stance on how to calculate tax owed by Apple is

stricter than guidelines by the Organization for Economic

Cooperation and Development, lawyers say, making it potentially

vulnerable in court.

Challenging the commission's methodology on calculating the claw

back size will likely be "a very important part" of appeals by

Apple and Ireland, said Jonas Koponen, global head of the antitrust

practice at law firm Linklaters. "The legality would hinge on

that."

Until those questions are resolved in court, the commission's

move could spawn widespread ambiguity for all sorts of

multinational companies operating in Europe, and relying on tax

arrangements similar to the one between Apple and Ireland.

So-called "comfort letters" are common, giving companies clarity on

how a country's specific tax laws will be applied.

"For many companies it creates uncertainty [around]... the

validity of tax rulings they have received in the past -- what

should they do?" Mr. Koponen said.

--Richard Rubin in Washington contributed to this article.

Write to Natalia Drozdiak at natalia.drozdiak@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 31, 2016 17:07 ET (21:07 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

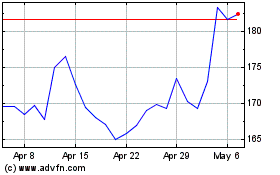

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

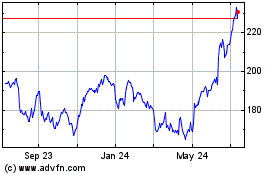

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024