By Richard Rubin

WASHINGTON -- American politicians have spent years salivating

over U.S. companies' stockpile of untaxed foreign profits, now more

than $2 trillion and growing.

This week, Europe got to that money pot first.

The European Commission's ruling that Apple Inc. must repay

$14.5 billion to Ireland represents a major threat to a bipartisan

U.S. tax agreement that has long seemed plausible but always sat

just out of reach.

U.S. lawmakers said Tuesday they hoped the move in Europe would

accelerate potential compromises in Congress, including a one-time

tax to free up otherwise inaccessible cash so companies could

invest in domestic projects and get money to shareholders. Under

that plan, the U.S. could use the windfall to rebuild roads and

bridges, cut tax rates or both.

But bitter partisan divides over how heavily the U.S. should tax

its own companies abroad continue to stymie efforts to revamp the

corporate tax code, barring a long-elusive breakthrough.

The commission said Apple used Irish rulings to pay an

artificially low tax rate on money that it earned all over

Europe.

To the U.S. Treasury and lawmakers in Congress, European

regulators represent a threat in part because companies could get

U.S. tax credits for increased payments abroad. The U.S. is trying

to protect its claim to the cash even though they haven't figured

out how to tax it yet.

U.S. companies have been accumulating foreign profits outside

the reach of the Internal Revenue Service because of the way the

U.S. tax system works. Companies headquartered in the U.S. owe the

full 35% U.S. corporate tax rate on the profits they earn around

the world. But they can get foreign tax credits for payments to

non-U.S. governments, and they don't have to pay the residual U.S.

tax until they bring the money home.

For example, consider a U.S. company that makes $1 billion in

the U.K., which has a 20% tax rate. The company would pay $200

million to the U.K., and it would owe another $150 million to the

U.S. if it repatriated the profits.

"Any ruling that is inconsistent with international tax

standards and harms American business abroad with retroactive

measures is inherently unfair and encroaches on U.S. tax

jurisdiction," said Sen. Orrin Hatch (R, Utah), chairman of the

Senate Finance Committee.

Sen. Charles Schumer of New York, the likely next Democratic

leader, called the EU's actions a "cheap money grab" that targets

U.S. businesses. Rep. Kevin Brady (R, Texas), chairman of the House

Ways and Means Committee, called the decision a "predatory and

naked tax grab" that highlights the need for major U.S. tax

changes.

"The EU is unfairly undermining our ability to compete

economically in Europe while grabbing tax revenues that should go

toward investment here in the United States," Mr. Schumer said.

"This is yet another example of why we need to reform the

international tax system to ensure these revenues come home."

That concern, however, doesn't mean U.S. policy makers will be

able to agree on what to do or that anything they do will calm down

the cross-border tension revealed by the Apple investigation.

"Superficially, it could be a motivation if people are concerned

about losing the opportunity to tax some of this deferred income,"

said Warren Payne, an adviser at Mayer Brown LLP and former

Republican policy director at the House Ways and Means Committee.

"But tax reform on its own is not going to protect U.S. companies

from this kind of behavior" by European regulators.

The current tax system encourages companies to find as low a

foreign tax rate as possible, book as much profit as possible

outside the U.S. and leave the money overseas. That is exactly what

they've done, and it has been particularly easy for technology and

pharmaceutical companies to move intellectual property outside the

U.S. and accumulate profits there.

Apple, for example, had $215 billion in cash and other liquid

investments outside the country as of June, up from $187 billion

last September. The company says it would pay a 33% tax rate on

part of that income if it brought the money home, suggesting it had

paid a single-digit tax rate abroad. CEO Tim Cook told The

Washington Post recently that the company won't bring the money

back "until there's a fair rate."

Until Apple changed its structure in 2015, the company used

subsidiaries that slid neatly between U.S. and Irish tax laws.

According to a 2013 U.S. Senate investigation, Ireland saw the

companies as resident in the U.S., because they were managed and

controlled from California. But the U.S. considered them foreign

entities not subject to immediate U.S. taxes, because they were

officially registered in Ireland.

"The way that the commission presented this decision in its

press release is fascinating," said Lilian Faulhaber, a tax law

professor at Georgetown University in Washington. "It calls out the

United States for not requiring Apple to pay more taxes. That is a

pretty targeted statement."

The U.S. Treasury has warned that the EU's investigation could

have a direct impact on U.S. revenue, because any taxes Ireland

collects could be credited against Apple's U.S. tax bill.

"At its root, the Commission's case is not about how much Apple

pays in taxes," Mr. Cook wrote in a letter to the company's

customers on Tuesday. "It is about which government collects the

money."

European governments should get the first chance to tax those

profits, and the U.S. is effectively trying to jump in line, said

Ed Kleinbard, former chief of staff of the congressional Joint

Committee on Taxation.

"The fact is that this revenue that's at stake here, this pot of

gold that's at stake, unquestionably arose in Europe in respect of

European activities," he said.

The U.S., however, hasn't been able to agree on what to do about

the stockpiled profits or about the foreign tax system going

forward. There is a general agreement on a one-time tax on those

profits as part of a transition to a revamped international tax

system.

But there's disagreement on what that tax rate should be, how

the money should be used, what the new system should look like, and

what other tax policy changes should accompany it.

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has talked

about using business tax changes to pay for infrastructure

investment, but she hasn't specified how that should work.

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump has proposed a 10%

tax on the accumulated profits.

House Republicans envision a transformed tax system that bases

corporate taxes on the location of sales, which would favor U.S.

exporters, tax imports and likely cause even more international

controversy.

Write to Richard Rubin at richard.rubin@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 30, 2016 13:15 ET (17:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

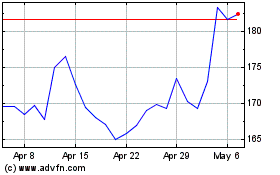

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

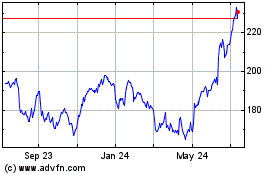

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024